Bulaobulao Aboriginal Village: The Root Vocational School

"Bulaubulau" originates from Atayal, meaning to wander or stroll. When travelers step into Hanxi Lane and enter the Bulaubulao Aboriginal Village in Yilan, they are surrounded by the essence of the tribe – ecology, vitality, productivity, life, and survival. The tribe's dedication to environmental protection, tribal operations, and talent cultivation over the past 20 years is also evident. This place, which follows the principle of tribal sustainability, has become a demonstration base for experiencing the ecology and culture of Taiwan's Indigenous people.

Live in Flow & Harmony with Nature

In 2004, Wilang Pan Chin-sheng, a Han Chinese man who worked as a landscape architect in Taipei, returned to his wife Saya's hometown in Hanxi, Yilan, searching for a different way of life. Along with six other tribal households, he fenced off 10 hectares of land as the base for establishing the Bulaubulao Aboriginal Village.

They adhered to the philosophy of "living in flow and harmony with nature" and ingeniously used ginger fields plagued by plant diseases and limited soil fertility to cultivate mushrooms. After four years, when the wood could no longer produce mushrooms, they planted ginger again, thus cycling back and forth in harmony with the land. They also grew various crops suitable for the area, such as millet, taro, pumpkin, and peanuts, without fertilizers or pesticides. The Bulaobulao Aboriginal Village gradually flourished into a small agricultural community; however, relying solely on agricultural exports was not enough to support the livelihood of the entire tribe. In June 2006, they opened the village up for guests to visit the mountain to taste freshly harvested dishes and experience the culture of tribal life. This would not only allow the good craftsmanship of the Atayal mothers to be passed down and shared but also keep young people working in the tribe. The resolve eventually developed into a comprehensive eco-tourism attraction.

When tourists enter the Bulaobulao Aboriginal Village, a clear and crisp "Lokah su! (How are you?)" breaks the serene, deep green surroundings. Here, you can stroll through the meadows, appreciate the houses that blend in with the natural landscape, and enjoy a culinary feast. They insist on low agricultural land development, only accommodating 30 guests per day, and not operating homestays so that both the tribespeople and the environment can maintain a balance and thrive.

Founding Inspiration

In 2009, Wilang's son, Kwali, who had studied hotel management and multimedia design in Australia, translated for a girls' soccer team from Hanxi Elementary School to participate in a soccer tournament in Hawaii.

He was moved by the symbiotic relationship between Brigham Young University-Hawaii (BYU-Hawaii) and its adjacent the Polynesian Cultural Center, which offers work opportunities for students to practice what they learn at school and help those in need become self-reliant.

Kwali recalled that tribal youths often lack mainstream educational opportunities due to insufficient resources. The model at BYU-Hawaii could support tribal youths' needs, and he believed that this educational model would bring them more opportunities.

In 2011, Kwali had the opportunity to host The Alliance Cultural Foundation (ACF) Chair Stanley Yen, and he expressed his ideas on alternative education for tribal youths. Chair Yen gave his support and recommended that Kwali apply for BYU-Hawaii's Asian Executive Management Program (AEMP). During the ten months of AEMP, Kwali gained a deeper understanding of the school's philosophy, further strengthening his ideas on education. After returning to Taiwan, he began applying to initiate The Root Vocational School.

Five Senses and Six Arts

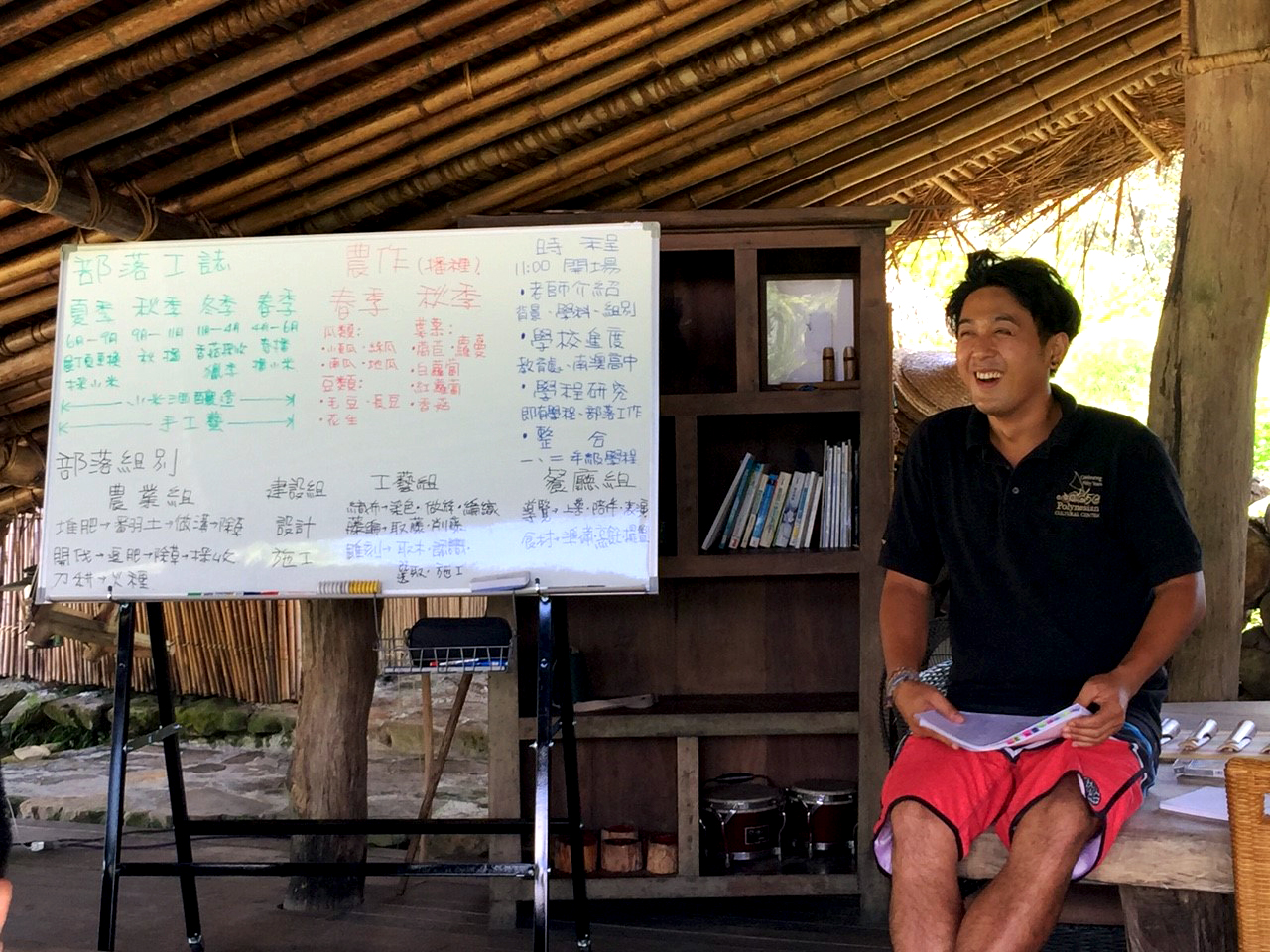

In May 2015, The Root Vocational School was officially approved by the Yilan County Government's Education Department. Kwali discovered the true value of education while studying in Hawaii – to equip young people with professional skills and character and to encourage them to leave the tribe and explore the world. He proposed the "Five Senses and Six Arts" concept, which allows students to deeply understand traditional Indigenous culture firsthand through their five senses of seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting, and to inherit the six traditional arts of singing, dancing, weaving, carving, tattooing, and cooking. In core subjects such as language, math, and science, Kwali wanted tribal youths to learn through non-mainstream educational methods. They host a volunteer teacher dinner in June and July every year, inviting teachers interested in teaching in the tribe to explain the tribe's operation status to them. The teachers then design courses that integrate tribal life and gradually encourage youths to step outside their comfort zones. In the first year, students are exposed to diverse topics and cultivate a love of learning. In the second year, they enter professional courses such as tattooing, bicycle repair, bartending, and baking. In the third year, they arrange for internships in the respective industries. Guiding the youths through a three-year learning journey, the composition of teachers and curriculum is tailored to the youths' talents and interests each year. The millet champagne "alïh," which can be found at Chef André Chiang's restaurant, RAW, is a result of the school's practical learning philosophy.

Kwali's sister, Merlers, developed several design and marketing ideas while interning at Fashion Designer Jamei Chen's studio and later founded the Bulao Goodgoods handicraft brand. Today, the brand has become a teaching platform for youths to realize their dreams in handicrafts.

To date, 20 graduates from The Root Vocational School have graduated, 70% of whom are employed in different units, and 30% of whom return to the tribe with their experiences.

"I feel the tribe should not emphasize how to encourage youths to return, but rather, to equip them with the confidence to step out," said Kwali. Through the school, he hopes for students to find the joy of learning, which he believes will take root in their hearts and guide them for life.

Kwali reflected on the graduate who decided to join the army. At first, he felt regret, but then remembered his founding intention of establishing the school and said, "Although the graduate chose not to stay in the tribe, it was still his choice in his life journey. At least we could give him the support and companionship he needed at that time of his life."

"Adults often expect youths to progress with the top-to-bottom approach, but I hope that youths can find their way from the bottom to the top," Kwali said.

When asked how many youths have shown improvement because of the school model, Kwali says, "We shouldn't have the framework of 'improvement' in the first place. Our approach is to spend time guiding the youths, assuring them that this is a safe space for them to learn and explore their abilities." Although Kwali does not have a definite answer for where the school will be in 3-5 years, he is confident that he will continue to guide the youths through the key stages of their lives and give them the confidence to find their future direction gradually.

In the past two years, The Root Vocational School has not recruited enough students, but Kwali says this is not necessarily a negative because it means fewer students dropping out of schools in the tribe. Youths from outside the tribe are also welcome to apply to the school – currently, three youths from single-parent families lack a sense of security, and volunteer teachers recommend students who are a good fit for the school. Kwali believes that as long as the youths are willing, they can apply during the enrollment period from April to June each year and have the opportunity to join the Bulaobulao family.

"Over the past seven years, with nearly 100 volunteer teachers, we have established connections with them. Sharing these resources with other tribes is the direction I have been striving for," Kwali said when asked whether the school's methods could be adopted in other remote areas. Kwali believes that if other remote areas do not follow the approach of The Root Vocational School, they may still develop their approach by starting with the youths' unique talents and addressing education from the bottom up.

He has a bold idea to establish an online platform that centralizes resources for experimental education in remote areas, allowing youths who cannot afford to learn not to miss out on the opportunity. Kwali hopes to link more educational resources to spread his influence more widely.

Throughout the pandemic, with no tourists visiting the village, Kwali said they focused on harvesting agricultural products for processing, such as pickling, making turnip cakes, dried bamboo shoots, etc. They also started an online shopping platform and attempted to deliver the products; however, some goods were spoiled when the customers received them. "We didn't know what cold chain technology was at the time. We called the chemistry teacher at The Root Vocational School and made adjustments to the production process so that the tribe could continue to operate during the difficult time.

"We are very fortunate to have so many kind-hearted people helping us on the road to establishing the Bulaobulao Aboriginal Village," said Kwali.

Over the past twenty years, the Bulaobulao Aboriginal Village has continuously adjusted and transformed, developed within limits, and preserved the tribe's original appearance. They guard the values and connotations of Indigenous peoples, coexist with nature in a way that cherishes it and maintain an open attitude towards the future.

When we, as travelers, step into the Bulaobulao Aboriginal Village, we are infected by their confidence and ease. They use music, singing, and attentive service to express their expectations and friendliness to travelers. This is where nature and culture are genuinely felt.

Photos provided by the Bulaobulao Aboriginal Village