Bulareyaung Dance Company – Finding Authenticity in Taitung

2020 marks the fifth anniversary of the Bulareyaung Dance Company (BDC). To commemorate the milestone, BDC performed works created over their five years in Taitung at Junyi School of Innovation's Wonderland Performing Arts Center. The Taitung way of life and culture were reflected in their song and dance. The same year, BDC was invited to teach body movement at the annual Gosh Creative Arts Camp, an Alliance Cultural Foundation (ACF) and Gosh Foundation collaboration.

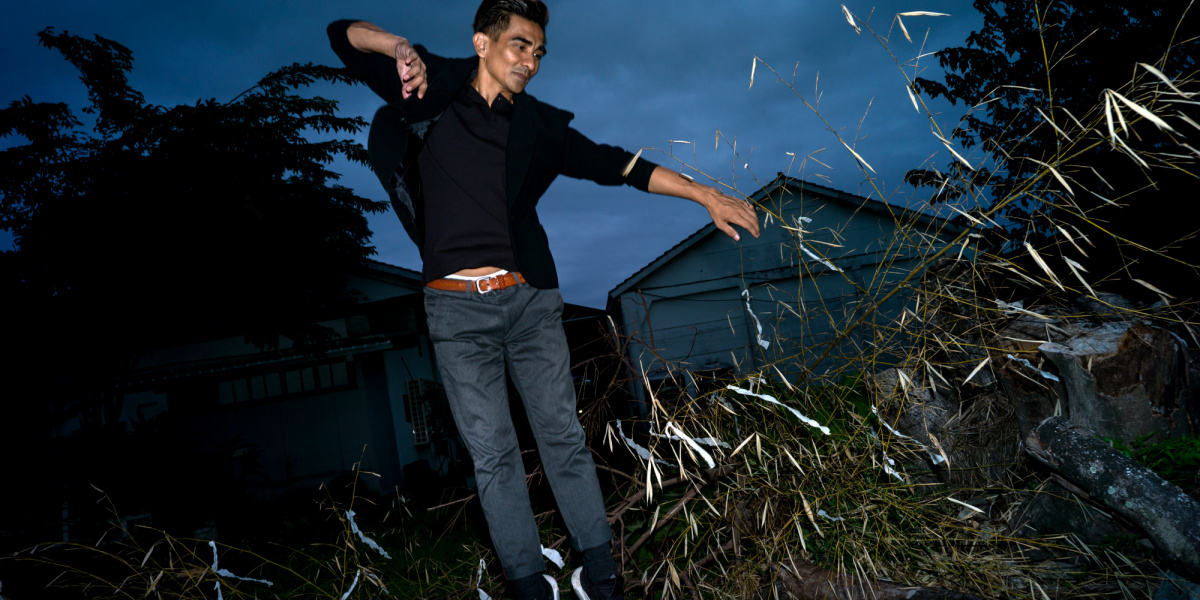

Across the field of grass is the BDC studio, once an old sugar warehouse. From the décor of the studio to its environment, the company has developed the ambiance of a true dance company over the years. BDC sings a traditional Buliblosan Village song, and their voices travel far past the studio walls. The bougainvillea backdrop shows the dimensions of Bulareyaung's gentle features—he is calm and steady.

2015 was the year of internationally acclaimed choreographer Bulareyaung's return to his birthplace, Taitung. It was there that he founded the BDC and built his studio in an old sugar warehouse. The first instruction he gave to his dancers was to hold hands. "Why do we hold hands? To hold onto what was lost." Bulareyaung reflects on this first instruction he gave.

From a young age, Bulareyaung left the Paiwan village. He grew up in the city to pursue education; his pursuit of dance brought him even further away from home. In 1995, though he legally changed his name from his Han Chinese name, Kuo Chun-Ming, to his Indigenous name, Bulareyaung Pagarlava, he felt no depth or authenticity behind the name.

I am Bulareyaung

"Though there are many regrets in my past, I feel content for moving back. Besides aspiring to establish an inventive dance company, I wanted to see whether I could be more Indigenous. This may sound odd because I am a native by birth, but it is because the education I received growing up was based on the Han culture, and when I later pursued dance, I chose styles – ballet and modern dance that were not in any way related to my native roots." Five years later, in Taitung, he no longer doubted his identity as a native, but rather, "I am Indigenous, I am in Taitung, I am Bulareyaung."

Over the years, he attended several Indigenous festivals, and it was there that he began to reconnect with his roots. Indigenous festivals were a fading custom from the Japanese colonial rule in 1895 until its gradual revival in 2000; for this reason, Bulareyaung did not have childhood memories of them. The first festival Bulareyaung attended was the Hunter Festival in 2012 with Indigenous singer Sangpuy Katatepan Mavaliyw at the Jhihben's Katratripulr Village. It was an occasion celebrated by the Beinan people. At the festival, Bulareyaung felt like a nervous young boy, anxious that he may unintentionally offend village traditions; however, whenever help was needed – from building tents to carrying stones, he was eager to lend a hand. When camping in the mountains, he reflected and asked himself, "Should I move back to Taitung? There is nothing here. Am I brave enough to move back? What if I lost my stage?"

Bulareyaung attends festivals whenever he has time. "I would join not only festivals from my village but festivals celebrated in my dancers' villages. We attend them because they give us a lot of inspiration." Much of his choreography today is inspired by the festivals. Because he experienced a loss of self and instrumentalization of his body in dance, he doesn't want his dancers to walk the same path. He was determined to unite modernity and tradition in his works. "In some aspect, we are very fortunate because we didn't lose ourselves completely." In total, there are 16 officially recognized tribes in Taiwan, and there are songs unique to each tribe and village. Over the last five years, BDC's works have been based on traditional Indigenous music and dance. Works such as La Song, Warriors, and Luna reflect Bulareyaung's process of reclaiming his roots. He created harmony between modern and traditional and hoped that in his efforts, his dancers would not have to endure the loss of self as he once had.

Bulareyaung's temperament shifted over the years. The once-criticizing perfectionist now adopts a loving yet strict approach to mentoring his dancers. "In the past, I had an awful temper. I was particularly intolerant when dancers struggled to carry out a move. I had the mentality of – if I can, why can't you? I was unforgiving and would have them practice over and over. Today, this is no longer the case; my dancers, who are in their early 20s, could be my children. I am still strict, but treat them with love and understanding." He feels that the natural environment of Taitung, his dancers, whom he treats as his children, and his age are all contributing factors. Bulareyaung once threw a pencil at one of his dancers, A-Mingming – when A-Mingming reflects on the day, the fear he then felt still lingers. "Thankfully, the age of pencil-throwing is over; when a mistake is made now, we simply just laugh it off."

When A-Mingming's dad fell ill, Bulareyaung allowed him to take a long leave to spend time with his family. Aulu, another dance member, reflected on the time when he had experienced a hard breakup and was crying himself to sleep every night, "Whenever I was in the studio, I would cry, and when I was tired from crying, I would sleep. Bulareyaung gave me the time and space to grieve the end of my relationship until the day he asked, 'You should feel better by now?' – and since that moment, I did." That was the moment Aulu realized Bulareyaung had been observing him the entire time. He was allowing him the time and space to release his emotions, and when the crying was done, it was time to dance.

"It is because of my dancers that I finally let go of the Taipei mentality." In the past, whatever Bulareyaung did was for a purpose. If there were a day that he didn't spend practicing in the studio, he would feel he was wasting his life away. "Today, if I don't feel like practicing, I will walk by the sea and enjoy the shore." The Bulareyaung today believe that though practice is important, living life has even more value. "My dancers are the ones that helped create this shift. When our bodies tell us they cannot continue – we either go by the ocean, creek, or mountains or, because they know my love for coffee – they would accompany me to have afternoon tea. Rehearsals are important, but living life has even more value."

Bulareyaung and several of his dancers once lived the city life in Taipei. When visiting today, they would realize they no longer connected with the place they once called home. "We are too accustomed to life here in Taitung and each other. When we visit friends in Taipei, we almost always go with other BDC members – otherwise, we find it boring," said Aulu and A-Mingming. In conversations that were once familiar with old acquaintances, Bulareyaung felt a sense of pressure and pessimism. "The first time I visited Taipei, I realized I was no longer used to life there. I strongly disliked the city I once loved. When I dine out with friends, the conversations would be negative – about what wasn't good enough in their lives… but I suppose this is also normal when we have expectations of how life should be, but I experienced a lot of pressure then." The spirit of the people is different. The people of Taitung have a helping spirit; whenever there is a need, there is a helping hand. The positive and giving spirit of the people fills him with appreciation each day – he feels Taitung has given him much more than he had ever had in Taipei.

When Bulareyaung decided to establish BDC, his mentor and founder of Cloud Gate Dance, Lin Hwai Min, suggested he use his name to preserve the reputation he had worked hard to build over the years. He would later learn that the people of Taitung had never heard of him. To increase ticket sales, BDC would promote their performances locally – in night markets and along street sides; they learned that if the people enjoyed a performance, they would return.

Bulareyaung believes that 99% of the people who watch their performance will appreciate it not because of his presence but because their performance connects with the audience through the honesty and vulnerability of the dancers. "Does this seem overly confident? But I say this because they appreciate it not because of 'Bulareyaung' but because they see a part of themselves in the act." What is unique about BDC's performances is that they attract audiences from all backgrounds without necessarily understanding dance but because the performance touches them. Because dancers display their vulnerabilities on stage, the audience uncovers their own vulnerabilities and is inspired to search deeper within themselves.

Unlike other dance groups that attract audiences with dance backgrounds and foundations, BDC established a completely different market. Bulareyaung jokes, "People who have backgrounds in dance are not our audience because they will soon discover that what BDC does isn't dancing." Watching a BDC performance without any knowledge of dance will still touch people in a way that will bring tears to their eyes.