"Dare to Dream, Hold On to Your Intention" --- Sakinu Ahronglong, Founder of Hunter School

Passionate about preserving Indigenous culture, Sakinu Ahronglong from the Paiwan tribe resigned from the Special Police First Headquarters in Taipei in 2002 to return to his birthplace of Laulauran, Taitung, to pursue his dreams. From writing, giving speeches, and working as a forest ranger to founding the Hunter School in 2002 and Cinunan Adventure Education in 2020, he hopes to bridge the lost connection between humans and nature through these endeavours.

A Childhood Rooted in Tradition

With a strong build and tanned figure, Sakinu speaks with charisma reminiscent of the power of the mountains and the delicacy of water. His childhood nickname, "Liguchu," which is Pinayuanan for "talkative" and "inquisitive," shows how Sakinu was a curious child who wanted to try everything.

Raised by his grandparents, he credits his love of writing to his grandfather's love of telling stories while he inherits his acute insight from his grandmother. Though he developed a fondness for writing from a young age, his teachers would remark that his logic was spotty, critiquing him with the proverb, "You can't make a silk purse out of a sow's ear," or "You can't sculpt with rotten wood." Sakinu would write in response, "But you can grow mushrooms from a sow's ear and rotten wood!"

Looking back, Sakinu comments, "Luckily, my teacher couldn't understand my writing, so I wasn't corrected." Growing up surrounded by tradition and culture, Sakinu retains his roots in his work, using his background to help inform the writing of his literature prize-winning novel. His successes show that what his teachers once thought was rotten wood actually had strong roots and branches, giving him a solid foundation for growth.

Nature is one of the many aspects of Sakinu that has found growth and inspiration. His father, Sakinu's hunting teacher, often tells Sakinu, "Our land is borrowed from our children." One time, when their neighbor cut down an old bishop wood tree, his father heart-rendingly asked the neighbor, "How could you sell our children's shade?" Carrying on his father's heart for the environment, Sakinu has planted over 120,000 trees on the land of the Hunter School over the years. He says, "I'm giving the world an invisible present – the gift of fresh air."

From a young age, Sakinu was well-grounded in the hunting culture of his ancestors. His father taught him the hunting wisdom and values of their tribe. Later on, he carried on this respect for hunting by professionally training with the National Police Agency's Special Police First Headquarters. It was there that he realized that not all hunters have the skills to pass on their experiences, and not all members of the Special Police First Headquarters value the spirit of hunting, with some viewing it as murder or an environmental hazard. To integrate these differences, Sakinu designed the classes at the Hunter School to focus on developing practical and culture-oriented hunting skills.

The first class, or "entering," prepares students to enter the forest physically and mentally. The second class, or "follow," teaches students to walk at a commutative pace, careful not to leave anyone behind. "Together," or his third class, teaches students to safeguard one another, to protect themselves and each other. His fourth class, or "I can do it," involves days of running and foresting in the woods to practice hunters' gathering and chasing abilities. The last class, or "clarity," allows students to enter the forest to nurture their connection with nature. Sakinu believes, "The purpose of the course is not solely to teach hunting skills but to teach the true spirit and heart of hunting. They are designed for students to reconnect with nature."

What motivates students to embark on this three-night, four-day trek with its mountaineering, camping, cycling, and wading challenges? From experience, Sakinu understands that extreme physical activity releases endorphins. This creates a situation where while a person's physical reserves are depleted, their mental state remains clearer than ever. Sakinu refers to this as the "peak experience," which he hopes each of his students will be able to experience. He says, "This 'peak experience' of overcoming limitations is the spirit of a hunter."

As a forest ranger, Sakinu is occasionally called to rescue lost or injured hikers. His peers often wonder where he finds the courage to surpass fear. He believes, "To overcome the fear of darkness, you must walk directly into the darkness." He teaches students to walk in complete darkness, treating the night as a companion. He hopes students embrace their fears as an opportunity to face them.

Sakinu believes that forest education will help rebuild human and nature's relationships. He hopes people will connect with the phrase, "Rain has emotion, trees can talk, and mountains have ears." Being connected with nature is the basic ability for hunters to learn to listen and wait.

The Hunter School classes were initially designed for young tribesmen. It was until Sakinu and his wife, Jane, had three daughters that she protested, "Girls should be allowed to experience the water, forest and darkness too!" Breaking tradition, he created the "Haohao Classroom of Women" to be able to pass on the wisdom of hunting to his daughters and other women. When women are in the forest, he finds their bravery no different from men.

When it comes to the impact of Sakinu's Hunter School is evident through the reflections of his students. Yichune from Taipei shares, "Knowing where to situate me in the mountains to be in a position to help others is such a valuable ability." Another student, Senayan, from the Papalu Pinuyumayan Community, shares, "I am ever grateful for the unconventional women-focused hunting classes. Who knew how much work it would be just to learn to walk a mountain!" Lakuz from the Falangaw Amis Community shares, "Sakinu often says a mother is a child's most important influence. He has taught me that if I want my child to be brave, I must first become a brave mother!"

Nini from Tainan brings yet another story. Always wanting to get close to the mountains but not through leisure hiking, Nini found the Hunter School classes to be a perfect fit for her desire for challenge. She realized that anyone can use the sky for sight, the earth for bedding and trees for rest. "You don't need an all-encompassing mountain gear to mountain climb; the mountain will tell you all of your needs." she reflects. Bakkan from the Miharasi Truku Community in Hualien likewise has found strength from conquering challenges with fellow women; as she says, "A gift and strength that no one can ever take away." Eleng, a mix of Rukai and Paiwan, shares, "I'm already at the age where children call me Ina (aunt). Even though I don't have experience being a mother, it's my calling to support mothers and children." While these women warriors have different personalities, they all hold the same air of determination, holding onto their inner understandings and convictions in the hunter culture.

After returning to his home village from serving in the Special Police First Headquarters, Sakinu put all his energy into the local youth village group. He opened his home to the village, and with the "Haohao Classroom of Women" next door, it seemed momentarily that all of Sakinu and his team's hard work had come to life. In 2019, however, disaster struck the night before Mother's Day. A vicious fire destroyed Sakinu's home and the "Haohao Classroom of Women"; it burned down the village's longtime meeting place and a neighboring church. Sakinu not only had to pay for his losses and the church's renovations but was ordered to attend classes on fire damage and public danger laws. Making light of the situation, Sakinu joked that since so few people were ordered to attend classes in Taitung for fire-related offences, he had to take the classes with those there for drunk driving.

How do you rebuild after encountering such adversity? Jane reflects on the day of the fire when she received a phone call from her daughter saying that their home had caught fire – uncontrollably and widespread. "I let the pressure and worry go shortly after," she said and recalled having to console family members' grief for the loss. The experience helped Jane let go of good and bad emotions to start over. It made her realize that time waits for no one and that she must keep moving forward. She remembers a friend of her young daughter exclaiming, "You've burned all the housing, clothes, books and toys you'd ever want in your afterlife!" Jane, a resilient woman warrior, smiled at this comment.

As for Sakinu, after the incident, his daughters often found him by the sea, wistfully looking on with grave sorrow. Sakinu believes that the mother sea healed him from the trauma. Three months later, he told himself, "Sakinu, you are a man of passion, energy, and resilience; don't be so easily defeated."

Today, Sakinu is able to laugh about what his Paelabang Danapan teacher told him when he came to visit Sakinu long after the disaster. Teacher Danapang could only muster a stuttered comfort of, "Oh yes, indeed, this is a huge fire…oh, Sakinu, you must be the first aboriginal to have burned down a church…"

Sakinu started rebuilding his village, remounding his mountain and preparing his classrooms and structures. Though he wished for his daughters' help, he failed to consider that as the girls grow older, they no longer want to follow their father's way. Jane talks of her daughter's sentiment of feeling wronged, "Over the New Year, while others were celebrating with fireworks. Our daughters were celebrating by clearing the rocks up the mountain hills." This tension lasted for about a year until Sakinu held a family meeting, openly expressing each other's thoughts and emotions. Sakinu apologized to his daughters, starting the practice of setting dates to spend time with them, such as having lunch together when his oldest daughter ends the school day, organizing a two-day, one-night nature trip with his second daughter, or riding bikes with his youngest daughter. Finding himself through adversity helped his family move forward with their journey.

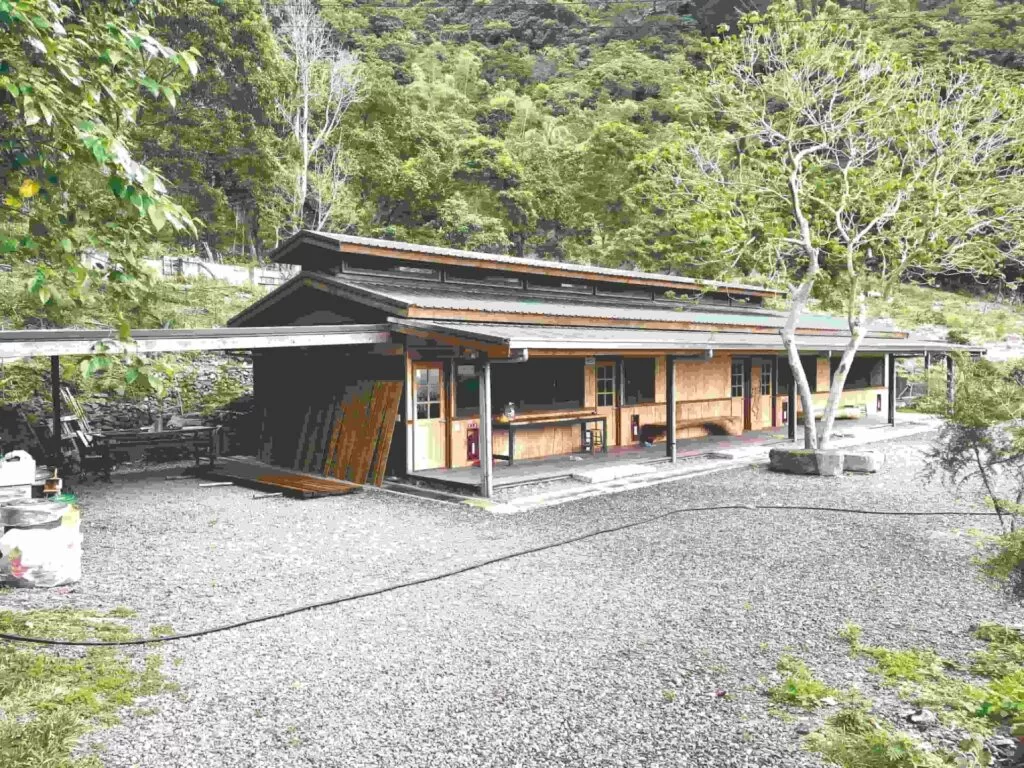

The fire incident also burned off some old habits. Before, Sakinu held onto an "if I won't do it, no one will" attitude towards his village work. Now, he can delegate and retire from his leadership roles in the Tribal Traditional Youth Union, recognizing that by letting go of his own will, he may be able to achieve more altogether. Finally rebuilt, the new Hunter School is noticeable from any angle, whether from the hills or the woods. Sakinu credits its perfect proportions and details to Jane, who used to work in an architect's office and has a natural eye for aesthetics and construction. She taught Sakinu how to design a blueprint, meticulously planning out every room, door, and window measurement – even so far as to the space needed to walk from the kitchen to the bathroom. With her caution and attentiveness to detail, they hope to find the right placement in the forest for their new house. When it comes to visuals, the couple designed a minimalist look, adding important traditional aboriginal elements within as finishing touches and allowing cultural freedom for modern expression.

Sakinu's new home has also been inspired by the essence of his travels. Such inspirations include Japanese interior architectural structures, traditional Filipino balconies, the Sami people in Norway's cultural preservation habitats, etc. In particular, his archery classroom's ventilation system was inspired by a time when Sakinu chased a criminal to a pig pen. At that time, he noticed how the roof's ventilation system was well-designed and thought out, giving Sakinu inspiration for his future constructions.

Hunter School

The Hunter School will soon open its doors to nearby schools, allowing nearby village children to experience its adventure and wonder. The program offers itself not on a tourist ban but on a limited educational visitational exchange. Welcoming other exchanges, Sakinu says, "The Hunter School isn't just for the Paiwan Lalauran village. As long as you want to learn about the wisdom of the forest, no matter your gender or race, you are welcome here."

Sakinu compares education to a plant needing a goal to reach; like how plants strive towards the sun, education must strive towards greatness. He believes that the best education doesn't just involve passing on and reviving the Paiwan culture; instead, he believes the power of education is far greater and able to push past the current shapes and limits of tradition, like how plants sprout from soil.

To Sakinu, "Changing tradition is actually just continuing the tradition." Preserving a culture is a road-heavy responsibility, but it is a part Sakinu accepts. He says, "Being able to all be a family, whether related by blood or not... this is what I want for the future Hunter School." This fostering of community has been long written in Sakinu's hunting notebook, showing his long-time dedication to the belief.

During the interview period, every morning, I saw Sakinu busy pulling weeds, planting seeds, moving bricks, and building the house. All moving toward his goal, his strong companion, Jane, tells me, "There is a giant that lives inside Sakinu's heart."

Like a giant, Sakinu's gaze is large enough to see the seas and mountains, and he dares to dream and remember why he started.